Introduction

I’ve had this TP-Link Archer MR600 for a while. It’s a decent LTE router, stable, compact, but like every “black box” device, I’ve always wondered: what’s really inside?

So, I decided to open it up and take a look. No fancy exploits, no remote attacks… just old-school hardware hacking.

Note: I politely asked the router for consent. It didn’t reply, so I gave myself permission to hack it.

Figure 1. TP-Link Archer MR600 – front side board

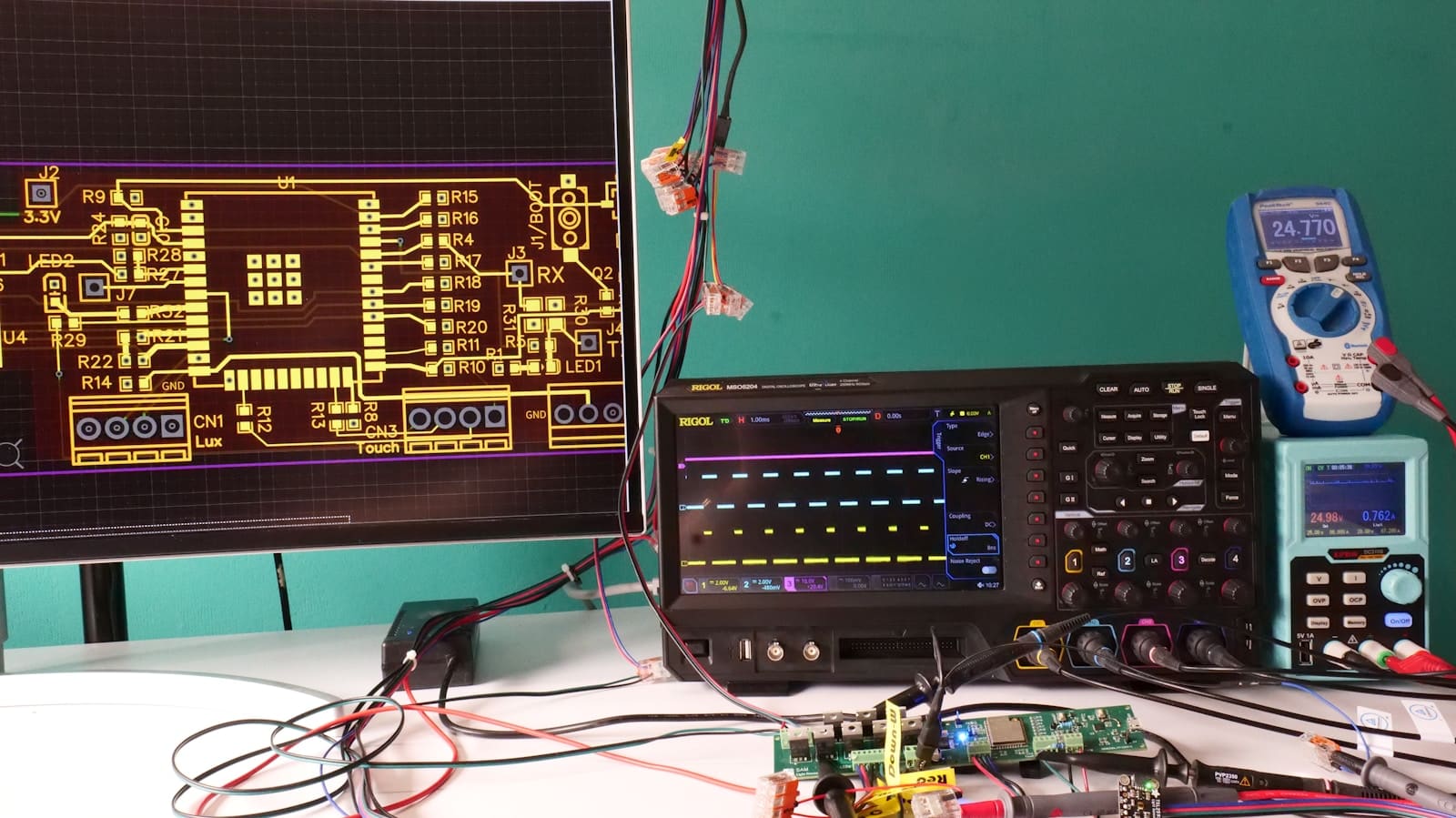

Finding the UART

First mission: locate the serial interface.

Right on the bottom, I instantly found the four-pin UART header, so I grabbed my multimeter and started probing:

•GND: continuity test to any shield point.

•VCC: constant 3.3V output, identified right away.

•TX: fluctuating voltage when powered on.

•RX: silent line waiting for input.

Figure 2. Bottom side board & UART interface

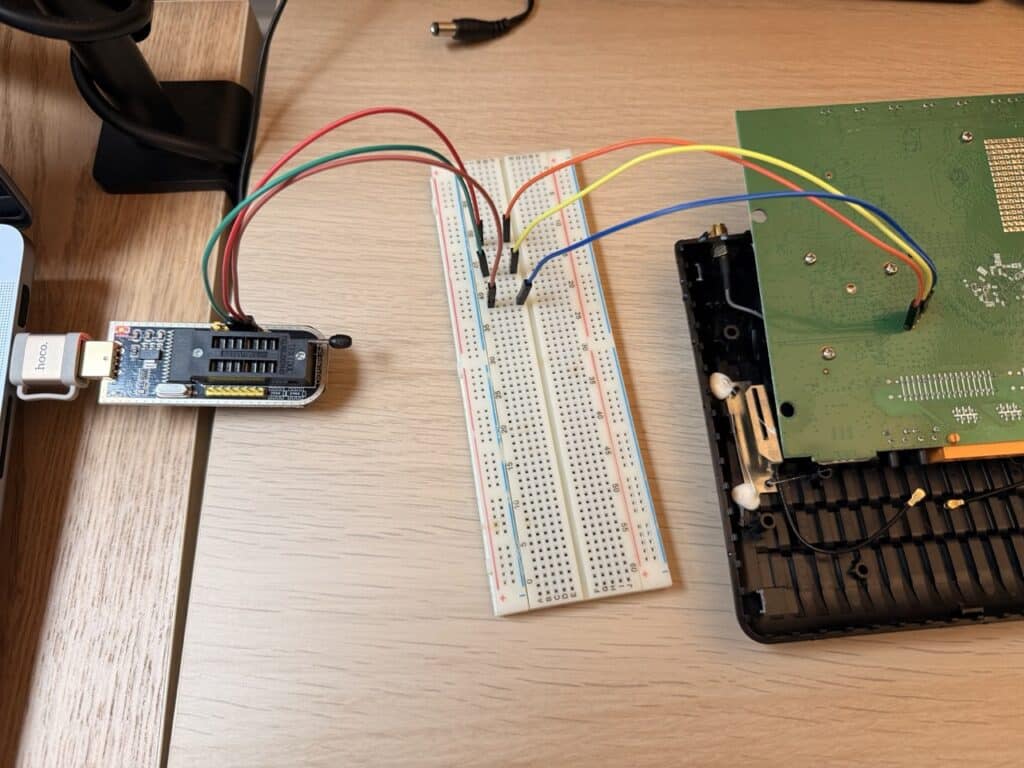

Once the pins were mapped, I grabbed few jumpers and connected them to my CH341A configured in TTL mode. I used a breadboard because I didn’t have any F-to-F jumpers.

Figure 3. UART interface & CH341A programmer wiring

Then I fired up:

screen /dev/ttyUSB0 115200

Alternatively you can use minicom:minicom -D /dev/ttyUSB0 -b 115200

115200 baud is the go-to rate for these chipsets.

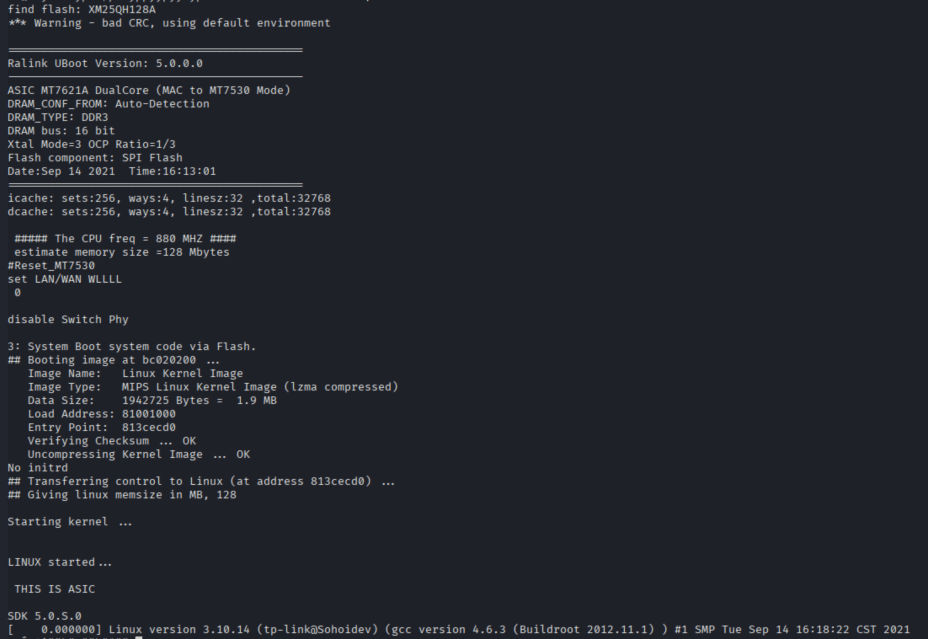

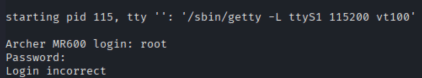

Watching it boot

After powering the router, the terminal came alive with logs, bootloader, kernel messages, everything.

I couldn’t interrupt the boot (the watchdog reset every time I pressed keys), but I could watch the full sequence until the familiar “login” line appeared.

Nice. So I started trying the usual suspects: root/root, admin/admin, admin/password… no luck.

Figure 4. Serial bootlog

Figure 5. Login prompt

If you can't get in, read the flash

Time for plan B.

If I can’t get in from the front door, I can still read what’s inside.

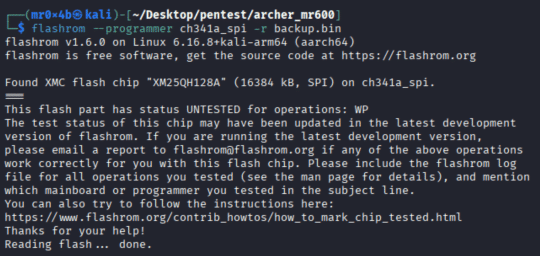

I removed the heatsinks on the front of the board and identified the flash chip. It was labeled XM25QH128A, a 128Mbit SPI NOR – datasheet confirmed 3.3V logic, standard pinout (reference: Alldatasheet.com).

So I switched the CH341A to SPI programmer mode, grabbed a SOIC8 clip, and went straight for the flash chip.

Figure 6. Heatsinks removed

Figure 7. Flash chip

Figure 8. XM25QH128A Flash

The router remained unpowered during this step (no dual power!). The CH341A supplied 3.3 V to the flash directly. I connected the SOIC8 clip – pin 1 orientation double-checked – and dumped the entire chip:

flashrom --programmer ch341a_spi -r backup.bin

A few minutes later: success.

Figure 9. SOIC8 clip wiring

Figure 10. Flash & CH341A wiring

Figure 11. flashrom firmware dump

Peeking inside

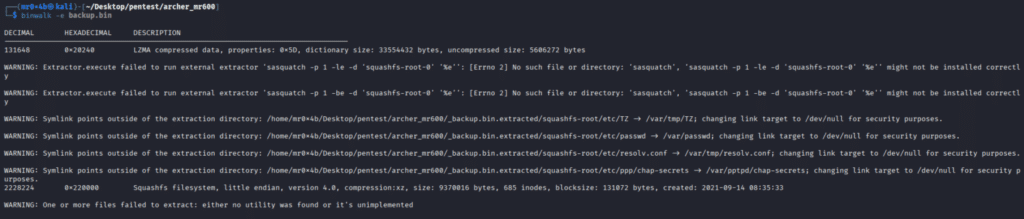

Next stop: binwalk.

binwalk -e backup.bin

It found a squashfs filesystem.

Figure 12. Binwalk extraction

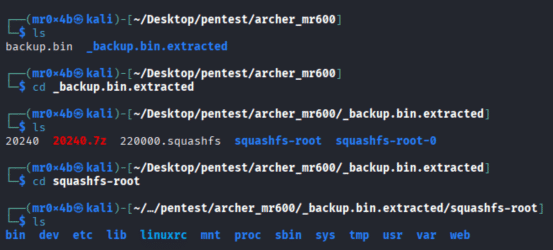

Once extracted, I explored the dumped files.

Figure 13. Exploring Squashfs

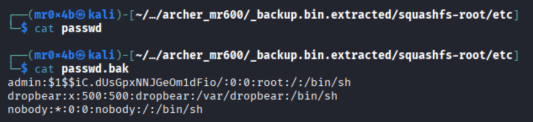

When I dove into /etc/, I found… an empty passwd file.

But another one caught my eye: /etc/passwd.bak.

Here’s what it contained:

Figure 14. passwd.bak file content

Interesting. An admin user with UID 0 – root privileges – and an old-school MD5 crypt hash.

Cracking the hash

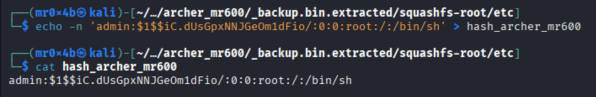

I grabbed that hash and saved it into a file:

Figure 15. Saving the admin MD5 hash

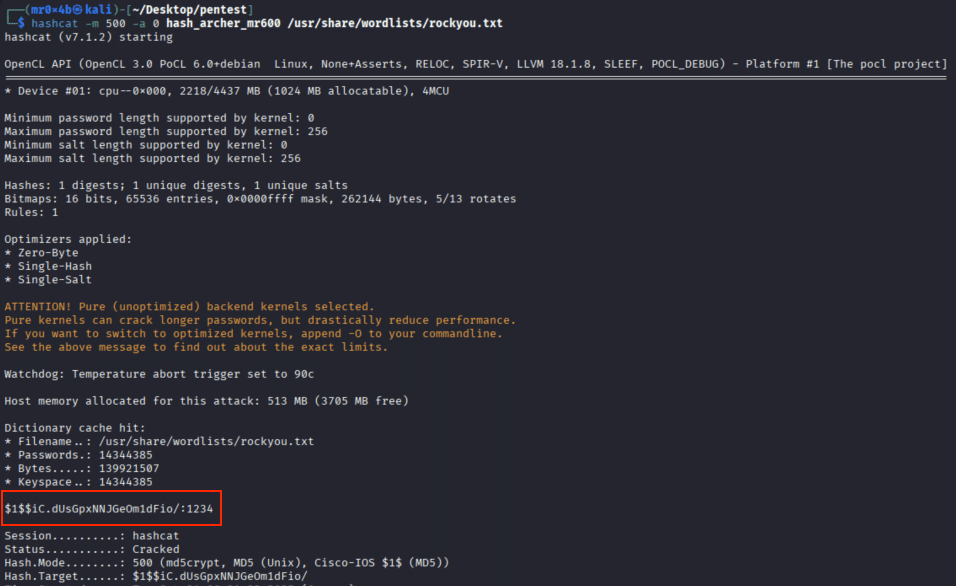

Then I fired up hashcat, and less than a second later I got the password:

Figure 16. Cracking the admin MD5 hash

Yup. The password was literally “1234“.

Back to the console

I flipped the CH341A back to TTL mode, reconnected the UART, powered on the router, and at the login prompt typed admin/1234.

And there it was: root shell access. I’m in!

Figure 17. Root login

What this means

This wasn’t about exploiting TP-Link remotely or finding a zero-day.

It’s about what happens when:

•physical access isn’t protected,

•credentials are stored in plain text inside firmware,

•and weak passwords are still a thing in 2025.

Even though this was my device, it highlights a broader issue: many consumer routers ship with leftover credentials or debug accounts in the firmware.

Lesson learned

•Physical access = full access. UART and SPI are powerful entry points.

•Weak hashes are still everywhere. $1$ (MD5-crypt) is ancient and fast to crack.

•Vendors should lock down debug accounts or enforce stronger password policies.

•Responsible curiosity is good. Research, document, share, and disclose ethically.